Of Asians Among the Abstractionists

New York Times Bibliography, April 4, 1997

Holland Cotter

One of the chief lessons taught by the ”new” art history is how richly impure a thing art is: a product of influences and coincidences rather than of spontaneous generation.

That idea is illuminated in a surprisingly beautiful exhibition at the Jane Voorhees Zimmerli Art Museum at Rutgers University titled ”Asian Traditions/Modern Expressions: Asian-American Artists and Abstraction 1945-1970,” and in a smaller satellite show at the Taipei Gallery in Manhattan.

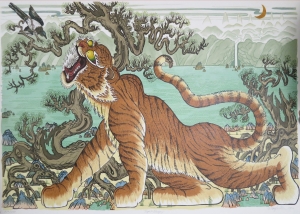

Much of the painting and sculpture is superbly imagined and executed. The surprise comes in discovering how few of the artists are familiar, even though their work ran on a parallel and often overlapping track with high-profile American abstraction of the postwar years.

Most of them were Asian-born; many had art training in China, Korea and Japan. Several were in the United States during the heyday of Abstract Expressionism, and might have expected to find an audience receptive to their modernizing of Asian art, already notable for its abstracting tendencies.

What they found, however, was an avant-garde intent upon forging an ”American” art, one that defined itself partly by playing down foreign precedents. Robert Motherwell’s expressionist calligraphic exercises were admired, but the work of an Asian artist adapting gestural abstraction to Asian themes was often regarded as an unsatisfactory pastiche.

“Asian Traditions/Modern Expressions,” organized by Jeffrey Wechsler, senior curator at the Zimmerli, makes a strong case for viewing Asian-American abstraction in a fresh light. He proposes that this art, centered in nature and meditative rather than assertive in spirit, has roots in a fundamentally Asian esthetic. And he suggests that the signature features of Abstract Expressionism (gestural brushwork, a restricted palette) had time-honored Asian precedents.

Certainly right from the first work at the Zimmerli, ”Sinking Star” (1967), by the Beijing-born painter Che Chuang, a dynamic hybrid art is in evidence. Clusters of abstract strokes and daubs sit beside brushed Chinese pictographs. The very media used, oil paint on rice paper and newsprint, blend Western and Asian practices.

The show is arranged in thematic sections focusing on transcultural themes. ”Ancient Philosophy in Modern Forms,” for example, includes an exuberant swiped and spattered ink painting by the Korean-born artist Don Ahn, inspired by Zen brushwork, and a luminous watercolor by Chi Chen (born in China in 1912) that brings 1960’s Color Field painting to mind but incorporates words of the Taoist sage Laotzu.

The idea that traditional East Asian painting, based on landscape and the written word, is never truly abstract is examined in the section titled ”Abstraction and Nature.” Diana Kan peppers her dark ink washes with little trees and houses to insure that the image keeps its identity as a mountainscape. Tadashi Sato’s tonally modulated oil painting of gray spheres on a white ground may look abstract but actually depicts water flowing over rocks.

A bridge to full abstraction comes in work by the Japanese-born Kenzo Okada (1902-1982), who showed in New York with Betty Parsons in the 1950’s and whose flattened forms are as much Western modernist as Asian. The same may be said of the paintings by James Suzuki named for works by Sibelius and Stravinsky, and Masatoyo Kishi’s paintings titled with numbers in classic New York School style.

The balance of the organic and the abstract takes concrete form in the Zimmerli selection of sculpture — the American-born Isamu Noguchi (1904-1988) and Minoru Niizuma are the strong presences here — installed in an attractive simulation of a dry garden. But the complex crossover patterns of Asian-American abstraction come across most forcefully in the show’s concluding section, devoted to the theme of calligraphy.

Here, as elsewhere in the show, the modern responses to a traditional form are astonishingly varied, ranging from Walasse Ting’s towering black acrylic-on-canvas ”Hommage a Goya,” with its apparent nod to Motherwell; to Wucius Wong’s ink-on-paper fusion of Western and Asian texts; to Che Chuang’s Mondrianesque diamond-shaped canvas with Chinese characters spelling the word ”love” and a heart painted at its center.

The exhibition includes a handful of historical works — album pages, scholar’s rocks — to make explicit the Asian roots of Asian-American art. And the fusion of past and present is also underscored in a pocket-version of ”Asian Traditions/ Modern Expressions” installed at the Taipei Gallery in Manhattan.

This show, organized by the Zimmerli, opens with a 1969 ink landscape in classical style by C. C. Wang. Mr. Wang, born in 1917, was trained in both Chinese and Western art, and the body of work he has produced is an object lesson in the very different spiritual and formal energies that distinguish Chinese painting from Western abstraction.

His small landscape at Taipei Gallery, innovative within a specifically Asian context, is complemented by works of somewhat younger artists: a lovely grid painting by Yuho Tseng in which geometric abstraction is enlivened with applications of gold leaf, and Ming Wang’s ”Respect for Tradition,” a calligraphic mandala in which writing and painting come indissolubly together.

Certainly the time is right for a show like ”Asian Traditions/Modern Expressions,” and the Zimmerli has seized the moment with insight and aplomb. Asian art is a growing presence in America, and the cosmopolitan flavor of modern and contemporary work is clear; many of the artists in this show are still hard at work and deserve a wide audience. But the reason to visit the Zimmerli these days is less for a history lesson than for the painting and sculpture itself, often scintillating, always thought-provoking and a little bit strange, as art should be.

“Asian Traditions/Modern Expressions: Asian-American Artists and Abstraction 1945-1970” remains at the Jane Voorhees Zimmerli Art Museum, Rutgers University, George and Hamilton Streets, New Brunswick, N.J., through July 31. It then travels to the Chicago Cultural Center, from Sept. 6 to Nov. 2, and the Fisher Gallery, University of Southern California, and the Japanese-American National Museum, both in Los Angeles, Dec. 10 to Feb. 14, 1998. The smaller show remains at Taipei Gallery, McGraw-Hill Building, 1221 Avenue of the Americas, at 48th Street, Manhattan, through May 9.