ART: TWO SHOWS SOUTH OF HOUSTON ST.

New York Times Bibliography, September 30, 1972

John Canaday

Anyone not yet familiar with the cluster of galleries just south of Houston Street can get a favorable impression of what goes on down there by visiting a couple of current exhibitions, Pat Steir’s, which opens today at Paley & Lowe to run until Oct. 18, and a double‐header of paintings by Tony King and Bruce Everett at O.K. Harris, closing next Satur day.

Pat Steir is a happy example of a large but quiet number of young American artists who have not felt obliged to ally themselves with one or another of the militant factions — hard‐edgers, neo‐dadaists, popists, minimalists, sharp‐focus realists, or any others—that have been quarreling over the bits and pieces of abstract ex pressionism’s shattered empire for the last 10 years. She has taken whatever suits her from several of these sources and has used it in whatever way she pleases in an art founded on, of all things, landscape.

This is eclecticism, if you wish, but let’s not listen to any of that term’s ugly overtones. It is quite true that within one of Miss Steir’s paintings—take one called “Three Green Days,” for instance—you can pick out elements apparently adopted from artists as different as Robert Rauschenberg and Agnes Martin, along with a passage of old‐time, drip drop‐dribble, a hint of minimal or serial diagrammatics and a very pretty little bird that may have flown in from just anywhere.

But Miss Steir can no more be accused of borrowing than a poet can be accused of plagiarizing because he has not invented his own vocabulary to express an individual sentiment. Whatever she uses, she uses in her own way for her own very personal communication with the observer.

Just why she is as good as she is, however, I can’t quite explain, a difficulty that contributes to my conviction that she is very good indeed. After you have analyzed any work of art to the limit, there is always an inexplicable residue, if the work is any good at all, that accounts for its being more than an exercise. Whatever that elusive quality is, Miss Steir has plenty of it.

Unfortunately, none of the work is adaptable to illustration here. The Paley & Lowe gallery is at 59 Wooster Street. A large banner hangs over the inconspicuous entrance to help you find it. Then you have to climb to the third floor. It’s worth it, and I would like to suggest paying special attention to the drawings, which speak more quietly but just as poetically as the paintings.

At O.K. Harris, 465 West Broadway, Tony King has turned out an exhibition of illusionistic painting that is quite literally the most complete in its optical deception that I have ever seen anywhere, including the great baroque perspective ceilings, on which you can hardly tell where three‐dimensional architecture ends and painted fantasies begin.

Mr. King’s absolutely flat canvases look like geometri cal reliefs and are so con vincing that even after you have touched them (which you mustn’t), it is easy to believe that it must be your fingers, not your eyes, that are being fooled.

This would be a pointless form of painting except that the pseudo‐reliefs are also at least as ornamental as the best‐shaped canvases. Mr. King is as satisfactory a designer as he is an amazing technician, and that’s going some.

The companion exhibition in the adjacent room also has to do with precisely defined realism (the specialty at O.K. Harris), but is a little more to be expected. Bruce Ever ett paints ordinary things (a glass doorknob, a bit of crumpled metal foil, a jumble of machine fragments) at magnified scale, resting in what seems to be a total vacuum that removes every slightest vestige of any modifying factor between the eye and the objects. The first impression is that they have been revealed in microscopic detail, but a second look can show that everything has been nicely cleaned up and even simplified into a kind of deadpan but rather attractive sterility.

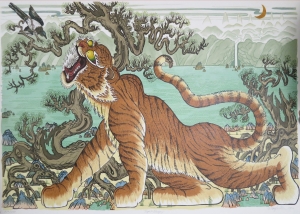

At the Green Mountain Gallery, 135 Greene Street, Dongkuk C. Ahn’s small group of orienlalish landscapes includes a series of writhing trees that were neither close enough to, nor far enough from, nature for my taste, and some other very nearly abstract visions of nature reduced to delicate broken lines that ring true to tradition yet hold their own as modern paintings. They make the gallery worth including in your tour.